Teresa Edgerton

author of fantasy

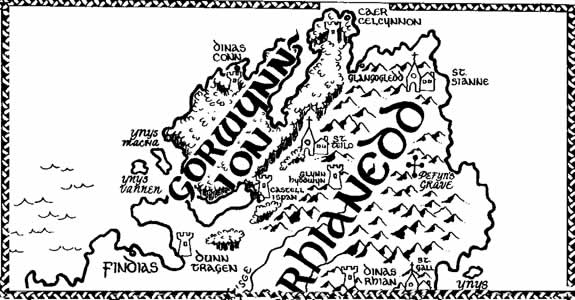

Lands

Ynys Celydonn - North

Caer Celcynnon

This family first came to the notice of the Old Ones, not because of the latent shape-shifting ability (which had been so long suppressed that even the Old Ones had all but forgotten it had ever existed) but because, in an overwhelming proportion, the Lords of Celcynnon and their immediate descendents bred true to physical type—this despite increasingly mixed blood. In stydying this phenomenon the pagan priesthood found much else to surprise them. First, that the shape-shifting ability was still strong in this line; later (though imperfectly understood) that this trait, unlike most other hereditary magical abilities, was sex-linked and highly dominant (as were the other characteristic Celcynnon traits) though more highly developed in some individuals than in others. The trait had apparently died out because (a) the daugthers did no carry it and therefore could not pass it on outside the family, (b) younger sons almost invariably joined the church or lived celibate by choice, keeping the trait almost exclusively in the direct male line where it was (c) fanatically repressed and never acknowledged.

In Celcynnon, sex is considered a filty and degrading business, but a necessary evil within marriage for eldest sons (who have a responsibility to produce healthy children to carry on God's work) and daughters (who have to marry and submit to their husbands beastly appetites in order to secure alliances, and because, being women and frail creatures at best, they might get into trouble otherwise). Thus, younger sons are envied and considered most fortunate because custom allows them the best opportunity for leading a pure, chaste life dedicated to God.

Dinas Rhian

Home of Cyndrywyn fab Dwnn, birthplace of Garanwyn and Gwenlliant. This fine old castle came to Cyndrywyn's father as an inheritance from his mother, the daughter of one of the oldest and most pure-blooded families in Rhianedd. Located at the top of one of Rhianedd's highest mountains, the site of the castle was, according to legend, one of Cynfarch's favorite retreats.

Findias

Ancient city in northern Draighen, long a center of wizardry and knowledge, later a prosperous trade center. It was near Findias, on an island in the Bay, that the great adept Atlendor established a school of wizardry, attracting some of the most talented young magicians in the realm, among them Rhufawn fab Rheged. A sensual man in his early years (he is said to have fathered over fifty children during his long life), he became at last totally devoted to the mind and intellect, seeking a way to maintain consciousness while permanently discarding his physical body. This was naturally accounted blasphemous, and he is therefore known as one of the three great fallen adepts. He gave up eating and drinking in hope that the body would wither and the mind remain, but suffering the final fatal stages of malnutrition he became confused and disoriented, thus proving, at least to his students' satisfaction, that mind and body were inseparably linked.

Glangogledd

Town in northern Rhianedd, second greatest port in the north. Known primarily for its frigid winters, it is mentioned often in poetry and song as the coldest place in the world.

Gorwynnion

Densely forested region, high elevation in the north, rugged cliffs plunging to the sea in coastal regions. Occupied by fishermen, hunters, and workers in wood, bone, and antler. Seals live and breed on the beaches and the coastal islands, but the Gorwynnach do not kill them (this is considered to be bad luck and tantamount to murder, for most of the common people believe in the Selkie-folk) and deal harshly with poachers.

The gods of Gorqynnion (in keeping with the climate) have always been harsh; the demanding pagan gods have given way to a Christian god cruel in his judgments, constantly demanding, and almost impossible to placate. But no one ever accuses the Gorwynnach of hypocrisy; they are even harder on themselves and their families than they are on strangers. Even among the Gorwynnach, the folk of Caer Celcynnon are regarded as fanatics. Fervent devotees of the old gods, from whom they were said to derive shape-shifting abilities, the Lords of Celcynnon have completely reversed themselves, becoming fanatical Christians and violently opposed to everything that even hints of witchcraft or paganism. It is like the Gorwynnach to do nothing by halves.

Cuileann, the local version of the Holly King (also known as Lord of the Wild Things), was one of the more benign Gorwynnach deities. Survivals of his cult can be detected (even in Celcynnon): the oak, holly, and mistletoe appear often as armorial bearings or crests in all the great families, and the arms of the Lords of Celcynnon were vert, a wolf's head erased, until Cuel replaced the wolf with the white hart of his vision.

Pefyn's Grave

Pefyn is a legendary hero who apparently traveled ceaselessly during his lifetime and may (if the evidence is to be believed) have continued as an itinerant even after his death. Throughout Celydonn, sites are named for him and his alleged deeds in each locale. Besides numerous Pefyn's Seats, Pefyn's Couches, Pefyn's Wells, Pefyn's Bridges, Pefyn's Forts, Pefyn's Drinking Cups, etc., etc., at least three different burial mounds have been designated Pefyn's Grave.

Rhianedd

Mostly rugged highlands, wooded (mostly pine and fir) mountains and glens, except in north and east. The Rhianeddi are shepherds and goatherders, hunters, fishermen, weavers and dyers of fine wool, and metalworkers (the mines yield ore of poorer quality than the mines of Gwyngelli), hunters, and fishermen. They were originally clan and tribal as in Cuan and Mochdreff but infinitely more complex. Chieftains of septs pledged loyalty to Clan Chiefs, who in turn were under the authority of the most powerful member of each Clan Confederation, who owed his ultimate loyalty to the King. Intense family pride, fierce rivalries but a strong sense of being one nation. The Rhianeddi as a whole are known to love ostentation and strive endlessly to acquire land and influence within the clan, sept, etc. These traits have always been exaggerated in the Kings and nobles. The divisive nature of conflicting ambitions probably accounts for their eventual domination by the south, in spite of the very defensive lay of the land and the strong sense of national identity.

The Rhianeddi, like most northerners, are deeply religious, but devote more energy to pomp and ceremony, prayer, fasting (but never for very long), and outward show than they do to improving themselves morally. Unlike the Gorwynnach, who place a great importance on penitence and penances but figure you'll probably burn anyway, the Rhianeddi sin, confess, receive absolution, and go back to what they were doing before with a clear conscience—the great thing for them is making certain that you don't actually die with too much unabsolved guilt.

When the High King's acquisition of the sacred relics (the Bones of the Ancient Kings of Rhianedd) made it absolutely necessary for the King of Rhianedd to win the High King's permission in order to reign, it became customary for the King's heirs to be fostered at the southern court (this custom was reestablished after Anwas's restoration), whence the custom among the Rhianeddi nobility to ape southern manners and styles. As the Lords of Rhianedd grew ever more estranged from their people (some, like Cadifor and Llochafor, not even speaking the language) and accordingly less popular among them, paranoia was added to the less admirable traits for which the Lords were known. It should be noted, however, that dispite mixed blood-lines and childhood upbringing that divorced them from their highland heritage, those characteristics for which they were best known were merely extreme extensions of the national character.

The Rhianeddi and the Gwyngellach are united by three characteristics: their common hatred and mistrust of the Mochdreffi, their flamboyant materialism, and their strong sense of identity with and love of the land (the latter two, besides giving them some ground for mutual understanding, also emphasize the alienness of the Mochdreffi, reenforcing the first, and principle, characteristic).

In Dinas Rhian and among Dyffryn's descendents the blood-lines were less diluted, due to intermarriage with families of purer, if less exalted blood, and because Dyffryn himself was something of a throwback, being the first (and in many ways) the most successful product of the Old One's attempts to breed the old talents back into the ruling families. His children and his grandchildren were all, for good or ill, remarkable.

The Raven of Rhianedd: associated with, but never positively identified as Cynfarch, an ancient prince of Rhianedd and one of the three great fallen adepts. Cynfarch gained control over the animal kingdom and led armies of wolves, eagled, and ravens into battle. A shape-shifter capable of taking on many forms, he particularly liked to take the shape of a raven, eventually (it was said) preferring that form to the human. Cynfarch's ravens had the gift of speech and the elders among them were said to be wise and skilled in simple magics; the Raven appeared periodically throughout subsequent Rhianeddi history, prophesying, advising, teaching, but never directly interfering in the course of events. By the reign of Cynwas, only one man lived who remembered meeting the Raven, and his very existence was widely doubted.

The High Priest of Rhianedd: in bygone days, he was subjected to ritual maiming (usually a cracked thighbone) at his initiation. There is some question as to whether this practice developed from an earlier custom whereby the priest chose his successor from among those already marked by accident or birth, or, in accordance with the Rhianeddi character, as a precaution against ambitious priests (usually near descendents of kings or princes) who might use their position and influence as stepping stones to the throne (see below as to why this was effective). One particular priest, who had no aptitude for the spiritual aspects of the priesthood but knew well the uses and misuses of power, inflicted so much suffering on the people that nearly the whole of Rhianedd converted to Christianity within something less than a century. Succumbing to (probably justified) paranoia, he neglected to name or train his own successor; at his death, there would have been none to succeed him had not a nameless woman appeared at the temple gate that same day, gave birth to a boy-child with a twisted leg, and promptly died. From then on, the more humane practice of choosing a born cripple for High Priest was established (or reestablished) and continued thereafter.

The King of Rhianedd: the ancient law decreed that the King must be without physical blemish, but because these kings were almost always warriors, as time passed, the custom was honored more in the breach than in the observance; no one wished to depose a strong and just ruler simply because he carried a few honorable battle-scars. But if the King was weak or unpopular, the very letter of the law was observed (Kings deposed under these circumstances rarely lived long), and even a great King could not continue to reign, and certainly no prince expected to be chosen, if he suffered any obvious disability.

St. Teilo

One of Celydonn's few indigenous saints and only genuine martyr. After the four evangelists (Maddiew, March, Lwch, and Sion), the most popular saint in Celydonn.